These Dark Days Are Filled With Light

This is the Wilderness We Choose; Our Lenten Journey, day 37

It is almost impossible to believe that we are almost at the end of Lent (for some Lent ends at dusk on Maundy Thursday and so it has ended already)! There is so much still that I would like to share and, although there is still a little time, I find myself quite giddy-headed with all that I would like to say, and also unequal to the task of quite conveying it. Holy Week has been a particularly deep and emotional one for me (in the best of ways), initiated by attending a Stations of the Cross service at my heart-church on Monday morning. I am going to try to write about that on Saturday but, for now, I thought that I would share a little about these three days; Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday, the journey through which I find deeply moving. I very much value the invitation of these days to rest in the broken dark & then to rise into wholeness & brightness like a seed.

Maundy Thursday (and the preceding days)

Maundy Thursday commemorates the Last Supper of Jesus and the Apostles, during which Jesus rises and washes the disciples’ feet. Once more, this is a deeply subversive act, especially coming as it does during a week when Jesus has, on Palm Sunday, ridden into Jerusalem on a borrowed donkey in an act of ‘non-violent pilgrimage’ explicitly designed to ridicule the authority of the Roman Empire and the complicity of the Temple.

On Holy Monday, Jesus ‘cleanses the temple’ by turning over the tables and chasing out the money lenders;

“And when he had made a scourge of small cords, he drove them all out of the temple, and the sheep, and the oxen; and poured out the changers' money, and overthrew the tables; And said unto them that sold doves, Take these things hence; make not my Father's house an house of merchandise.”

(John 2: 15-16)

Not only turning over the tables, but turning the world upside down; decentering Capitalism, which had firmly got its foot in the door of the sacred sanctuary. Jesus also accuses the Temple of stealing, specifically from poor widows. In the Bible verses above, Jesus particularly singles out the dove sellers. This was because it was doves that were sacrificed by the poor, most usually women, who could not afford more expensive sacrifices. Matthew, Mark, and Luke are all clear that this event was the catalyst for Jesus’ death less than a week later.

On Holy Wednesday, also known as Spy Wednesday, Jesus is in Bethany and Mary anoints his head and feet with spikenard, an extremely costly oil. This angers the disciples who believe that the oil should have been sold to help the poor. Judas though would like to keep the money for himself and, seeing the oil ‘wasted’, he seeks out the Sanhedrin, the religious authorities, and offers to betray Jesus for money.

Holy Wednesday marks the beginning of the Tenebrae services, which take place on the last three days of Holy Week. Coming from the Latin for ‘darkness’, Tenebrae services see the gradual extinguishing of candles with a loud noise taking place at the very end of the service when the light has gone out. In Malta this day is known as ‘L-Erbgħa tat-Tniebri’, or Wednesday of Shadows, again rooted in the Latin for darkness, and in the past children would drum on chairs to create the sound of a thunderstorm during church services.

In the Czech Republic Holy Wednesday is known as Ugly Wednesday, Soot-Sweeping Wednesday or Black Wednesday, because this was the day when chimneys would be swept to be in order to be clean for Easter. In Sweden, this day is ‘dymmelonsdag’, from dymbil (a piece of wood). On this day, the metal clappers in church bells would be replaced with dymbrils to deaden the sound.

There is such a sense in the days of life winding down, of the light going out.

And then we come to Maundy Thursday, the washing of the disciples’ feet, and the Last Supper.

The hospitality customs of ancient cultures, particularly those where sandals are worn, is to offer guests the opportunity to wash their feet, or to provide a servant to do so. For Jesus to choose to do this for his followers was yet another act of ‘turning the world upside down’, and is the source of the commandment to ‘love one another as I have loved you’ (John 13). The name ‘Maundy’ derives from the Latin, ‘Mandatum novum’, which translates as ‘new commandment’). Ken Sehested, in his meditation on Maundy Thursday, writes that, “Servanthood in the manner of Jesus involves relinquishing private interests in favor of covenant ties to the welfare of the community.”

Poet, Andrea Skevington movingly reflects upon whether Jesus also washed the feet of Judas, despite already knowing that he had betrayed him.

Jesus washes Judas’ feet.

That moment, when you knelt before him,

took off his sandals, readied the water,

did you look up? Search his eyes?

Find in them some love, some trace

of all that had passed between you?

As you washed his feet, holding them in your hand,

watching the cool water soak away the dirt,

feeling bones through hard skin,

you knew he would leave the lit room,

and slip out into the dark night.

And yet, with these small daily things –

with washing, with breaking and sharing bread,

you reached out your hand, touched, fed.

Look, the kingdom is like this:

as small as a mustard seed, as yeast,

a box of treasure hidden away beneath the dirt.

See how such things become charged,

mighty, when so full of love. This is the way.

In that moment, when silence ebbed between you,

and you wrapped a towel around your waist;

when you knew, and he knew, what would be,

you knelt before him, even so, and took off

his sandals, and gently washed his feet.

I am grateful to Diana Butler Bass for introducing me to this poem. You can read her reflections on Maundy Thursday here.

Thursday of Holy Week also commemorates the Last Supper; the final meal that Jesus shared with his friends, the meal that invited us to the Eucharist (the sharing of bread and wine). It is not an accident that this event took place during Passover, which remembers the story of the Hebrews’ escape from slavery in Egypt. But this Passover the people were again in bondage, this time subjugated by Roman occupation. Attacks against the Roman authorities increased at this time, as did attempts by those authorities to assert their domination. In the midst of this, Jesus again and again humbles himself to serve others and to declare himself as non-violent. And, he instigates the Communion during which we will all receive our ‘daily bread’, no matter how poor, how excluded, or how broken. Lydia Wylie-Kellerman writes that, at the Last Supper Jesus, aware of a world in which so many bodies starve and are brutalised, “gathered with his friends and taking the simple food before him, claimed his body as his own, and gave it as a gift”. A true act of resistance.

On Maundy Thursday a ceremony takes place during which all adornments are removed from churches; the ‘Stripping of the Altar’. Once bare, altars in some churches are washed with a bunch of hyssop dipped in wine and water.

Hyssop has been used for purification and healing since classical antiquity. In Leviticus it is used for the purification of lepers, at Passover it was used to sprinkle the blood of the sacrificial lamb on doorposts, and a hyssop branch is used to offer Jesus a drink of wine vinegar on the cross.

Immediately after the Last Supper, Jesus goes to the garden of Gethsemane on the Mount of Olives to pray. It is here that he is betrayed by Judas with a kiss and is arrested by the Roman authorities. He takes with him Peter, James, and John and asks them, “Please, stay here, and stay awake with me.” Three times he goes a little distance away to pray, knowing what is about to happen to him, three times he returns and finds them asleep. There are so many people in the world around us now suffering deep injustice. Maundy Thursday reminds us that we need to wake up.

Maundy Thursday by Malcolm Guite

Here is the source of every sacrament,

The all-transforming presence of the Lord,

Replenishing our every element

Remaking us in his creative Word.

For here the earth herself gives bread and wine,

The air delights to bear his Spirit’s speech,

The fire dances where the candles shine,

The waters cleanse us with His gentle touch.

And here He shows the full extent of love

To us whose love is always incomplete,

In vain we search the heavens high above,

The God of love is kneeling at our feet.

Though we betray Him, though it is the night.

He meets us here and loves us into light.

Good Friday

And so, we come to Good Friday and the day of the Crucifixion. I want to write about how the story of that day belongs to many different people, but that is for another day. For now, I want to share two Good Friday traditions that ground us in our own land.

Hot Cross Buns

Here in the Hedgehermitage we like to begin our Good Friday by breakfasting on hot cross buns, a traditional Good ('good' from the Old English for holy) Friday food.

The well known rhyme, "Hot cross buns, hot cross buns, one a penny, two a penny, hot cross buns" is an old street-sellers' cry. Bakers would have been awake all night and and town venders would have been out on the streets before dawn to make the most of the once-a-year opportunity to sell these delicious treats. It seems to say much about these sorrowful days that they are nevertheless filled with sweetness & light. The all in all.

Hot cross buns are sweet spiced fruit buns eaten to signal the end of Lent, with the cross on top representing the crucifixion & the spices the substances used to prepare Christ's body for the tomb. It is believed that cakes marked with a cross were baked in Ancient Greece, Rome, & Egypt, with the bun itself representing the full moon and the cross dividing it into lunar quarters. As the timing of Easter is woven into the closest full moon to Spring Equinox this also seems appropriate for this holy day. Our own familiar hot cross buns are said to have originated from the baking of Br. Thomas Rodcliffe, a 14thC monk of St Albans Abbey who created a similar recipe known as 'Alban buns'. These were distributed to the poor every Good Friday from 1361 onwards.

There is a great deal of folklore attached to hot cross buns. It was believed that buns baked & sold on Good Friday wouldn't spoil & they were often kept so that a small piece could be given to anyone who fell ill in the subsequent year. If hung in a kitchen they were believed to protect against fire & misfortune. Similarly they would prevent shipwrecks if taken on sea voyages. A woman in the Cambridgeshire Fenlands kept her Good Friday bread in a tin to bring good luck to her family until it was replaced with a new loaf the following Good Friday, then moistened, rebaked, & eaten, with the last slice thrown in the River Ouse to protect against floods.

One of my favourite books, 'Cattern Cakes & Old Lace' tells us that a hot cross bun has been hung up in a pub called The Widow's Son in the London Docklands every year since the 19thC. The buns now total over 200 & commemorate a woman who lived on the site & baked a hot cross bun each year in the expectation of her sailor son, who had been lost at sea, returning. Part of the pub's lease says that a sailor must hang a bun each year in her memory.

Sweetness in the dark.

Washing the Molly Grime

Fox-and-cubs, also known as orange hawkweed, devil's paintbrush, and grim-the-collier, may have little to do with Easter but my first meeting with them did lead me on a trail that brought me to one of our most fascinating Good Friday customs; the Washing of Molly Grime.

Fox-and-cubs is a member of the daisy family native to the mountain regions of Southern & Central Europe, where it is protected in some regions. It was introduced into UK gardens in the 1620s, and is recorded as an escapee into the wild by the 1790s. Its now found throughout much of the country, although it is rarer in the East and the South, which is why I feel especially blessed to have seen it at all. Its leaves form a rosette at the base of the long, thin stem, which is covered in short, stiff, black hairs. At the top are to be found 2 to 25 flowerheads all in a tight little bundle. This is where the name fox-and-cubs comes from ~ the unopened buds/cubs sheltering behind the fox-red open flowers, the foxes. Isn't that a gorgeous image. All parts of the plant exude a milky juice; a born protective mother. It also nurtures many pollinators, such as bees and butterflies, as although their orange-red colour is almost invisible to bees (hence so few orange wildflowers), the flowers absorb ultraviolet which makes them nicely conspicuous. To my eye they positively glow!

But it was its strange alternative common name, grim-the-collier, that led me to Molly Grime. The name comes from the plant's black, hairy stem, which looks a little as though it has been sprinkled with coal dust.

'Grim the Collier of Croyden' was a play first published in 1662 and concerned a character then already familiar from folklore and recorded even into the present day in landscape features such as Grim's Ditch and Grime's Graves. The origin of the name 'Grim' is unclear but many etymologists believe that it comes from the Old Norse 'Grimr', an Anglo-Saxon alias for the god Woden, a being who became conflated with the Devil, and attracted the name Grim (Old Norse for 'blackness') when incoming Christianisation caused the people to reject the Old Gods.

But, whist researching all of this, I was discovered 'Molly Grime'; a mysterious echo of the Sacred Feminine to be found in a (possibly pre-Norman) women's ceremony enacted until the mid-nineteenth century on Good Friday in the Church of St Peter in Glentham, North Lincolnshire.

On that day seven poor spinsters of the village would go to the local well to collect water which they would then process for two miles to the church to wash a medieval effigy known as the 'Molly Grime'.

It has been explained away as part of a deal struck with a local landowner over land rents but it feels much older and wilder than that.

One interpretation is that it derives from the Catholic practice of washing holy effigies. The church at Glentham was originally dedicated to Our Lady of Sorrows and so, on Good Friday, an effigy of Christ was washed and his ‘byre strewn with spring flowers’ (Winn, Notes and Queries 1888-9). This practice was known in the local dialect as ‘Malgraen’, which translates as ‘holy image washing’.

Another thread comes from the origin of the Molly Grime herself. It’s believed that she comes from the grave of Lady Anne Tourney, who belonged to a local wealthy family and who may have provided a small bequest to ensure that her tomb was washed each year. This seems believable but would not explain why the elderly spinsters walked so far to get well water when there must have been clean water much more easily accessible nearby. The water instead was brought from Newell Well, which was believed to have magical healing properties. One was that anyone who drank from the well would never move away from Glentham; a reminder of how important it is to belong to place.

Somehow all these threads have become entwined with very little hope of disentangling them; an example of the challenges of seeking the origins of folk traditions!

Nevertheless, the washing of Molly Grime does echo other European festivals, such as the washing of Saint Sarah, also known as Sara-la-Kali, or Sara the Black, patron saint of the Romani people said to have arrived in France as the servant of the ‘Three Marys’ who fled Jerusalem after the Crucifixion. On her Feast Day, 24th May, an effigy of the goddess/saint is taken to the sea in Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, Southern France and washed in the salt water.

‘Washing’ holy effigies at this time of year is also reminiscent of several such traditions in Eastern Europe, such as the ‘drowning’ of the Marzanna in Poland and elsewhere, in order to send away the winter and welcome in the spring. You can read more about that in my previous blog, ‘The Old Woman of Spring’, here. It feels important to remind ourselves that 'Molly' is a colloquial name for Mary and that 'Grime' is rooted in the Old Norse word for 'blackness'. In France, there is Sara the Black. Here we have Black Mary.

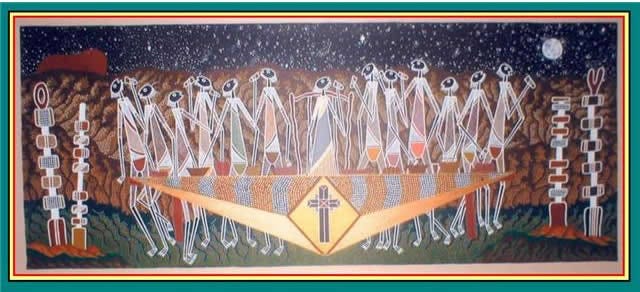

I love this quiet underground story of Molly Grime and the women who washed her with holy water each Good Friday. They remind me that women are at the heart of the Easter story, as mothers and lovers, loyal and steadfast friends, as myrhh-bearers, witnesses, and truth tellers. The men left. The women stayed. The white male God has much to answer for and takes us on a path that leads to the death of hope at the hands of Empire. But there is an older, wilder story threading its way through these days; a story of of rich, fecund earth, the darkness of the tomb-womb, and of resistance and resurrection. And, in our land at least, Black Mary, the Old Goddess shining in the dark, is at its heart.

May we rest in peaceful contemplation with our wild subversive Christ and his mother, Black Mary in the tender days ahead. What more powerful time to sit in the dark than when we are longing for the light? What more powerful a call to wake from our long sleep and to stand against the domination and greed that has infiltrated our holy of holies? Lent has ended and there is food to share. Everyone is welcome at the table. The candles are going out, but the light is always returning.

References:

Beautiful. You’ve helped make this Lent one of the most beautiful, ever!!!

Thank you for sharing this Lenten journey with us, it has been a truly beautiful experience. Read this mornings whilst eating my hot cross buns. Blessings from my hearth to yours 🌀🧡💜🧡🌀