We are in the midst of the nine days of Baba Dochia, the old woman of spring. In Romanian mythology, Baba Dochia represents the final struggle between winter and spring, a struggle which is echoed in our own folklore as the Cailleach and Brigid change places as the light returns.

Baba Dochia, or The Old Dokia, personifies our impatience for spring to come in. She is sometimes imagined as an old woman who insults the month of March when she takes out her herd of sheep or goats having assumed that spring has come. Thus insulted, March takes some days from February in revenge and brings back the winter cold. There are several different folktales which describe Dochia’s foolhardy ways.

In the first; the Legend of Dragomir, Dochia treats her daughter-in-law cruelly by sending her to gather berries in the forest at the end of February. This is an impossible task and the young woman is suffering from the cold, but God appears as an old man and helps her to complete the task. Seeing the berries, Dochia believes that spring has come and takes her herd onto the mountain in the company of her son, Dragomir. She dresses herself in twelve lambskins for the journey, but the winter rain soaks them and they become so heavy that she is forced to discard them one by one. Now unprotected, she perishes in the cold. Her son also dies, with a piece of ice in his mouth as he is playing the flute.

In an alternative version of her story, Baba Dochia has a son named Dragobete who marries against his mother’s wishes. Because of this, Dochia sends the young woman to the river to wash a black sheep’s fleece until it becomes white. Of course, the task is impossible, the girl’s hands begin to freeze in the river water and she weeps at the thought of never seeing her husband again. Jesus takes pity on her and offers her a red flower to wash the fleece with. Having washed the fleece white, the girl returns home and, again, Dochia believes that spring has come when she sees the red flower. She leaves for the mountain wearing nine coats. In the warm weather she becomes too hot and takes off the coats one by one, but the weather changes suddenly and she again freezes. The nine days from 1st to 9th March, when Dochia brings snowstorms just as spring is beginning, are each associated with one of her coats and are known as the ‘Old Ladies’ Days’.

Interestingly, Dragobete also gives his name to a festival held in Romania each 24th February. Echoing Valentine’s Day, it’s believed that if boys don’t meet a girl they like by Dragobete they will have bad luck all year. The customs of the day relate to the themes of love and healing. It’s said that Dragobete was considered so kind a young man that the Virgin Mary chose him to be the Guardian of Love and so his festival marks the day when birds become betrothed and begin to build their nests. At one time, young women would collect snow during Dragobete and this would be melted to be be used in healing potions throughout the year. Later, it was believed that merely taking part in the festivities would protect someone from illness, particularly fevers, in the year to come.

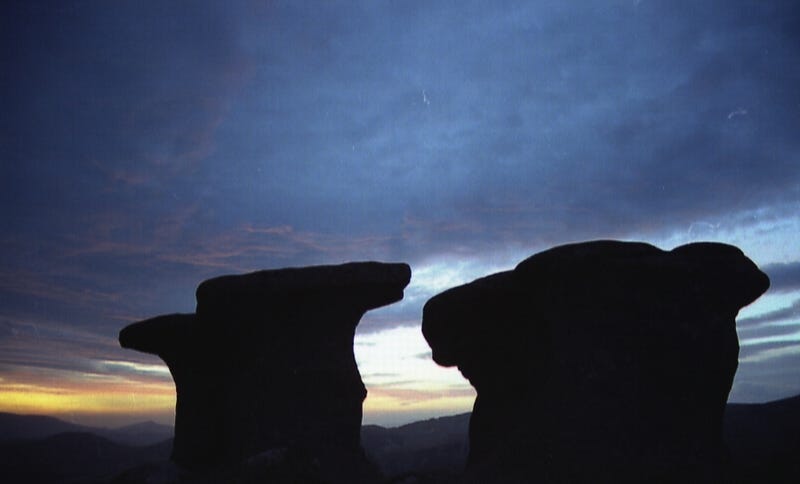

In the Romanian language, the plural of ‘baba’, meaning the hag or old woman, is ‘babele’, a name given to a landscape feature in the Southern Carpathian mountains. In this version of her story, Dochia is the daughter of Decebalus, King of Dacians, at a time when the Roman Emperor, Trajan, is attempting to take over part of the kingdom. He wishes to marry Dochia and, to avoid this, she takes to the mountain with her people, disguised as a shepherd and her sheep. Realising that she cannot get away she prays to the Dacian god, Zamolxes to turn her and the herd to stone. This is how they become Babele, a name given to a group of mushroom shaped rocks in the Bucegi Mountains.

In Bulgaria, we find Baba Marta, who also personifies the final tussle between winter and spring and whose day is similarly celebrated on 1st March, or in older traditions on the March new moon. This time, Baba Marta (Grandmother March), is said to be always bickering with her two brothers, January and February, but it is necessary for them to reach agreement with one another because the sun will only come out when Baba Marta smiles’ Without that the spring cannot return. In some stories, Baba Marta shakes out her feather mattress whilst she is spring cleaning and the feathers cover the ground like snow. This echoes the Frau Holle legend found in Germany.

My favourite version of her story again involves her brothers (or her husbands), January and February, but this time they represeny the long-horned beetle and the short long-horned beetle respectively, who are always drunk on wine, much to Granny March’s dissatisfaction. Because of their goings on, Baba Marta rarely smiles and the weather remains stormy. In another, an old shepherd takes her flock into the mountains believing that Baba Marta, as a fellow old lady, will smile on her and bring her good weather. But Baba Marta, insulted at being considered old asks her younger brother, April for a few extra days to bring ice and snow just when people might begin to believe that her powers are waning. In Romania, these are known as "zaemnitsi", or the "borrowed days". These stories truly convey the unsettled, liminal feeling of the edge of the season and remind us not to rush ahead but to sit with what is.

So unsure is it that spring will return that Baba Marta is also celebrated on both 9th March, the last of the Old Ladies Days, and 25th March, the Feast of the Annunciation (and here in England, Lady Day (of which more as Lent continues). These extra dates offer further opportunities to calm Baba Marta’s temper and bring the sun back.

Baba Marta gives her name to the festivals of Martenitsa in Bulgaria, Mărțișor in Romania, and Moldova and Martinka in North Macedonia. In all these traditions bands or figures of red and white thread are made. These are then given away to loved ones and worn around the wrist or on the clothes. In the mountain regions houses are decorated and domestic animals are given ‘martenitsi’ as a form of blessing and protection. The white and red threads represent man and woman, or sometimes the intertwining of summer and winter, and are often worn until a particular sign of spring, such as the return of swallows or the first blossom, is seen. The martenitsi might then be tied to a tree, as a gift for migratory birds, or placed under a rock, with the type of insects found there acting as an omen of the year ahead. Again, divination is a theme of these edge-of-spring festivals, with each of the nine Old Ladies Days of Baba Dochia offering opportunities for predicting the year ahead.

Returning to our theme of Lent, we find the Eastern Slavic festival of Maslenitsa, also known as Butter Lady, Butter Week, Crepe Week, and Cheesefare Week. Resembling our Shrovetide and Pancake Day, Maslenitsa is celebrated in the week before Lent begins. It is marked by sleigh rides, visiting of friends and family, and so the reinforcing of community bonds after the long winter dark, and the making and sharing blini or crepes, particularly with the poor. The Sunday of Butter Week is known as ‘Forgiveness Sunday’, where people will ask one another for forgiveness and offer small gifts. This is also the day when ‘Lady Maslenitsa’, a straw effigy decorated with rags, will be burned, her destruction signalling the chasing away of winter and the coming of spring. Her ashes will then be buried in the snow to bless the crops. Straw is considered a representation of winter in many Northern and Eastern European customs, including in England with the Whittlesey Straw Bear, which happens on Plough Tuesday (just after Twelfth Night), and in similar forms throughout the continent, often during Shrovetide.

Many of these traditions now have a veneer of Christianity, and whilst I love the intertwining of belief, it is good to feel the power of the Marzanna traditions of Poland, also known as Morė (in Lithuanian), Marena (in Russian), Mara (in Ukrainian), Morana (in Czech, Slovene and Serbo-Croatian), Morena (in Slovak and Macedonian) or Mora (in Bulgarian). Here is a being who brings together all the spring traditions in deep time. Ancient goddess of winter’s death, rebirth, and dreams, she becomes the spring goddess, Kostroma (which is also the name of the pole on which Lady Maslenitsa is held high), Lada, or Vesna. Although her celebration, which takes place at the Spring Equinox, has now become more secular it is still possible to see the ripples of a tradition that is older than old. On her day, handmade Marzanna, accompanied by children carrying green juniper twigs, are carried to a local body of water where the Marzanna are thrown in to be ‘drowned’. Often they will be dipped into every puddle and stream on the way. Sometimes they are also set on fire or their clothes ripped.

As the procession returns to the village, trees are decorated with ribbons and blown egg shells and the beginning of spring is celebrated with a feast. Mirroring Palm Sunday, the procession will be carrying bundles of branches and green twigs called ‘gaik’ in Polish, which translates as ‘copse’. This ‘copse’ is also known as grove, new summer, or walking with the Queen and, before the Spring Equinox date was chosen in the 20th Century, this took place on the fourth Sunday of Lent, much closer to May Day. This shifting of dates to fit in with different religions and traditions may explain why so many customs of spring and early May, or even into June, emulate one another, depending on how far north they are held. We can almost watch the greening of the land as the spring makes its way slowly northwards on the tide of the year. But, whatever the tradition or the religion, we find resurrection at their heart and the turning towards life.

Despite the Synod of Poznań, held in 1420, instructing the Polish clergy not to, “allow the superstitious Sunday custom”, or to “permit them to carry around the effigy they call Death and drown it in puddles”, the Marzanna tradition has survived in the Czech Republic, Poland, Lithuania, and Slovakia. In the 18th Century there were attempts to introduce a new custom of throwing an effigy of Judas from a clock tower on the Wednesday before Easter, but this was also ignored. It seems that the Old Woman of Spring, representing life coming from death, has a firm grip on both the weather and our psyches. As we in the British Isles contemplate a week of cold weather ahead, we might think of her during these nine days of Lent.

References:

Baba Dochia ~ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baba_Dochia

Babele ~ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Babele

Dragobete ~ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dragobete

Baba Marta ~ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baba_Marta

Baba Marta Day ~ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baba_Marta_Day

Mărțișor ~ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mărțișor

Martenitsa ~ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Martenitsa

Maslenitsa ~ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maslenitsa

Whittlesey Straw Bear ~ https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Whittlesey#Whittlesea_Straw_Bear

European Straw Bear traditions ~ https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Straw_bear

The death of Winter and the birth of Spring. So powerful that no decree of religion can stop the need for people to mark the transition (and ensure that it takes place?) This year Old Lady March is so grumpy that I have made Martinista to hang on my trees and charm the Old Lady to make up her mind. Maybe if more of us in the UK did that we would not be shivering under our blankets.

Thank you for this Bee - and certainly the (not really - listen, I'm honouring you!)'Old Lady' sounds like she's going to wave her fists at us over the next week, just as the lambs I'm helping with (in the smallest and least hands on of ways) need her warm smiles... Absolutely fascinating.