The Goose Saints: Resurrection, Reciprocity, & Rewilding

This is the Wilderness We Choose; our Lenten Journey, day 3

Yesterday, 23rd February, was the Feast Day of St Mildburh (also known as Milburga and Milburgh), 8th Century Benedictine abbess of Wenlock Priory in Shropshire. She was the daughter of King Merewalh of Mercia and his Queen, Domne Eafe of Kent. She was the older sister of Saints Mildrith (or Mildred) of Thanet and Mildgytha of Northumbria. The three sisters are sometimes said to personify the three theological virtues of faith, hope, and charity.

Mildburh has many fascinating legends attached to her. Like many of the female saints she has power over water. Refusing marriage to a prince from a neighbouring kingdom, Mildburh escaped across a river. The prince was unable to pursue her when the river became so high that it was impossible to cross. It’s also said that, when one day she fell from her horse, she was able gather water to bathe her wounds from a spring that appeared when her horse’s hoof hit a nearby rock; a story which often appears in relation to the pre-Reformation saints to explain landscape features. A church and holy well dedicated to her now stand on the site. The well later became a place for washing clothes and the water was said to cure sore eyes.

Mildburh also had a well in Much Wenlock, Shropshire dedicated to her, of which Catherine Milnes Gaskell, in her 1905 book, ‘Spring in a Shropshire Abbey’, writes;

“It is said that at Much Wenlock on “Holy Thursday”, high revels were held formerly at St. Milburgha’s Well; that the young men after service in church bore green branches round the town, and that they stopped at last before St. Milburgha’s Well. There, it is alleged, the maidens threw in crooked pins and “wished” for sweethearts. Round the well, young men drank toasts in beer brewed from water collected from the church roof, while the women sipped sugar and water, and ate cakes. After many songs and much merriment, the day ended with games such as “Pop the Green Man down”, “Sally Water”, and “The Bull in the Ring”, which games were followed by country dances such as “The Merry Millers of Ludlow”, “John, come and kiss me”, “Tom Tizler”, “Put your smock o’ Monday”…

I do love seasonal saintly shenanigans! In the same book, Catherine writes that one day she met a local child, Fanny Milner, who had been sent to the well by her grandmother to collect water for healing her sore eyes so that she could read scripture on Sunday. Fanny tells her that,

“It be blessed water, grandam says, and was washed in by a saint – and when saints meddle with water, they makes, grandam says, a better job of it than any doctor, let him be fit to bursting with learning.”

There are a good many saints who ‘meddle with water’. Another is Saint Eanswythe (630-650CE), my own local saint here in Folkestone, who is said to have made water run uphill to her nunnery, reported to have been the first religious house of women in England. The stream is still there and is known as ‘St Eanswythe’s Water’.

But Mildburh and Eanswythe have something else in common; they are said to hold a mysterious power over birds.

Both Mildburh and Eanswythe are credited with protecting their crops, which were being stripped bare by geese, by persuading the birds to graze elsewhere. So respectful were the geese of St Mildburh that they are said not to alight on the ground on her Feast Day in her memory.

Mildburh is particularly interesting in relation to crops. Gardeners and farmers in Shropshire once invoked her name for protection of their fruit, crops and fields. One of her legends suggests that she fed the local people during the ‘hungry gap’, which coincides with Lent and which we will be exploring more deeply on another day, when she caused barley sown in February to sprout, ripen, and be harvested in one day. There is some evidence that Mildburh is intertwined with the memory of a local goddess. Medievalist Pamela Berger writes that, "this saint was chosen to fill the role of grain protectress in Shropshire when the ancient pagan protectress could no longer be venerated."

Even more extraordinarily, Mildburh is said to have brought a child back to life when his other brought her baby to the saint in desperation. And the theme of resurrection brings me to one of my favourite goose saints, Werburgh. I have written more about her history, and about other saints who negotiated with wild birds for precious natural resources, on my previous blog, which you can read here.

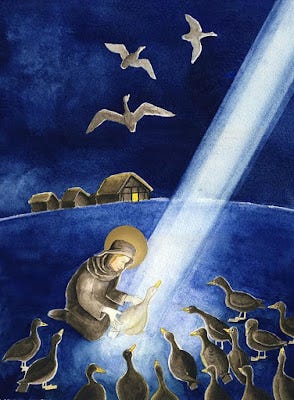

St Werburgh, whose Feast Day is at Candlemas on 3rd February, was an Anglo-Saxon princess born around 650 CE in Stone, Mercia (now in Staffordshire). She discovered one day that a large flock of geese at her abbey in Weedon, Northamptonshire was destroying her growing corn by feasting on it. To prevent this she gathered them up and began to keep them as though they were domestic geese. One morning, she called them to send them out for day but they refused to leave because one of their flock was missing. When Werburgh found that the goose had been eaten by her servants she demanded that the feathers and bones of the bird be brought to her.

Having been gathered, she prayed over the remains and commanded that the goose should live; much like La Loba, Bone Woman, singing over the bones of dead creatures in Clarissa Pinkola Estes' 'Women Who Run With the Wolves'. The geese were, of course, delighted, cheering and crying out at the return of their lost sister. Werburgh quieted them & asked that no goose should ever enter that field again, but agreed that they might freely graze on surrounding land. On gaining their agreement she set them free to become wild geese once more and, from that day to this, their promise has been kept. So deeply connected was she with geese that the pilgrimage badge given to those who visited her shrine depicted five geese in a wattle enclosure.

In Werburgh’s story, and those of other crop protecting saints, we find a mutual contract between humankind & the wild, one which at its heart carries the requirement to share what we have without resentment, rather than believing that everything on the Earth is here for our own benefit, or fearing that we might suffer a lack. In the telling, it's often suggested that the saints ‘command’ wild beings to comply but, looking more closely, we find a more subtle negotiation, an acknowledgement that other-than-human beings have right and agency, and a creating of bonds of reciprocity.

Here too is a story of rewilding. At first, Werburgh thinks to control the geese by safely cloistering them in her convent. When she realises that she can't guarantee their survival she liberates them, because it matters more that they live than that she guarantees her own security. This is a reminder of how delicately balanced our relationship with all other-than-human beings can be, and that, especially in this age of climate change, our decisions must be based in mutual benefit for all beings, not just for us (and only a small number of us at that!). We aren't only individuals, a society, or even a species. But we are a community; part of a web of wellbeing and co-operation. The saints remind us, and if they don't then the geese certainly will!

It is also worth reflecting on the thought that the 'Wild Goose', an Geadh-Glas in Gaelic, Geif Gwyllt in Welsh, is the name that Celtic Christians are said to have given to the Holy Spirit, perfectly embracing the untameable, free, & unpredictable nature of our connection to the indwelling Divine. There is little proof that the name was used before the 1940s but, for me, that doesn't discount the symbol. Christianity comes from a land of dry desert & wide open spaces where, perhaps, things are more obvious. Here, it finds itself responding to a landscape of green misty valleys & sea fog, of ever-changing tides & sheets of grey rain. Nothing is obvious here. Rather, like the Grail, it is only half-glimpsed before it's gone and we are lucky if we can catch a feather or two to reassure us that it was here at all. In the goose, Spirit is embodied in the form of a wild bird bridging water, earth, & sky, and that image is a vision of both God & land.

For our ancestors their goose would probably have been a Greylag, like this one encountered in my boat living days.

The Greylag is the ancestor of our domestic goose, having been domesticated as early as 1360BCE. The connection of the goose to the Divine is long. She is associated with the Sumerian healer Goddess, Gula, the Egyptian Sun God, Ra, & the love Goddess Aphrodite of Greece, where goose fat was once used as an aphrodisiac.

During Lent we are wandering in the wilderness, not with a tamed & domesticated God but with one who is destined to accompany us as we stand against oppressive and entrenched power, a power that responded to his turning over of the tables and entreaty for us to love one another as we love ourselves with fear and violence. That power underestimated the continuing ability of that Love to turn the world upside down, then and now as the story lives itself out again and again in our beleaguered world. Again, how we might interpret the story is all in the telling. Lent invites us to decide which side we are on. In the meantime, the goose, and her companion saints, are a perfect reminder that we wait for a Wilder God than we might have imagined.

Great Spirit, Wild Goose of the Holy One.

Be my eye in the dark places;

Be my flight in the trapped places;

Be my host in the wild places;

Be my brood in the barren places;

Be my formation in the lost places.

Ray Simpson, Community of Aidan & Hilda, Holy Island of Lindisfarne.

References:

St Mildburh

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mildburh

https://orthochristian.com/77751.html

https://pravoslavie.ru/77751.html

https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/members-area/past-lives/st-milburga/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stoke_St._Milborough

https://stmilburgas.org/st-milburga/

https://www.shrewsburyorthodox.com/events/23-february-milburga-of-wenlock/

http://www.shrewsburyorthodox.com/local-saints/saint-milburga/

https://www.thetablet.co.uk/blogs/1/2335/st-milburga-pious-posh-and-sadly-lost

https://tishfarrell.com/tag/st-milburga/

https://www.cooksinfo.com/st-milburga-day

St Eanswythe

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eanswith

https://findingeanswythe.uk/eanswythe/legends/

St Werburgh

https://radicalhoneybee.blogspot.com/2019/11/st-werburgh-resurrection-reciprocity.html

https://aclerkofoxford.blogspot.com/…/st-werburgh-and-goose…

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Werburgh

https://www.weedonbec-village.co.uk/uploads/walk-3-general-text-qr-9.pdf

https://wikimili.com/en/Werburgh

http://pilgrimsandposies.blogspot.com/2013/02/st-werburghs-day.html

http://orthochristian.com/77344.html

https://www.festivalstoke.co.uk/werburgh--the-wild-goose.html

St Mildrid

http://www.pravoslavie.ru/80901.html

https://aclerkofoxford.blogspot.com/…/st-mildred-of-thanet-…

La Loba

https://www.wilderutopia.com/…/la-loba-wild-woman-luminous…/

This is perfect Lent reading Jacqueline, and beautifully written and researched as always! Thank you xx

Sometimes a wild god ❤️ always a treat, thank you x