There’s the tree that never grew,

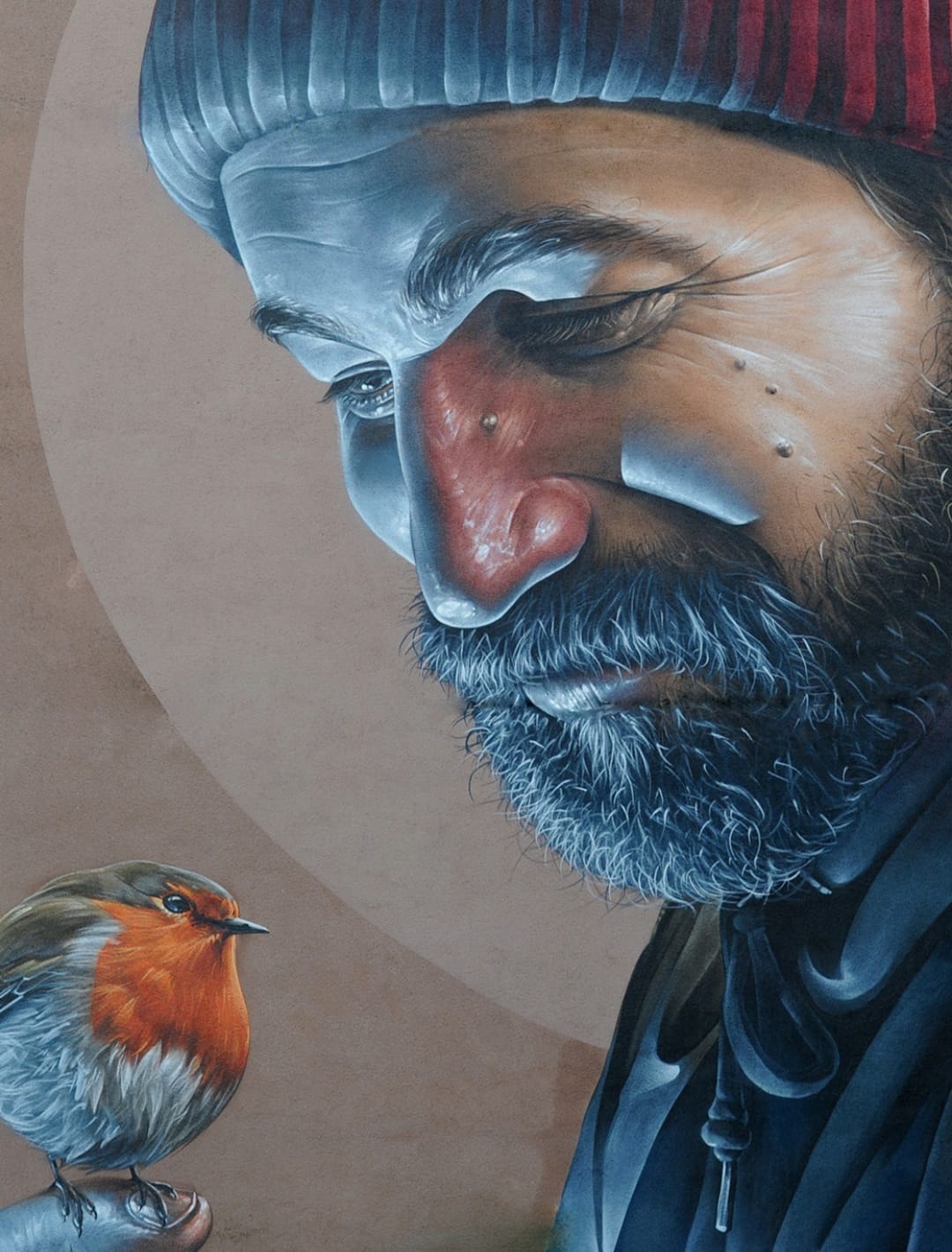

There’s the bird that never flew,

There’s the fish that never swam,

There’s the bell that never rang...

In 2020 I read a book called 'The Ten Thousand Doors of January' by Alix E. Harrow about doors we can step through to access other worlds. For me, what I call the wild antlered saints are also doors, invitations into a new learning, a different way of thinking, a soft nest of comfort to settle into, or into a landscape; a wild council of plants, animals, birds, insects, rocks, and prayer.

This landscape is untamed. The saints have not always belonged to the Church, and it was not always in the Church's gift to decide who was worthy of sainthood. Once, the people decided and lived within a yearly wheel of folk saints' feast days, many 'invented' to allow merrymaking during the long fasts of Lent & Advent, or to dignify the drudgery of work and to remind those in 'authority' where the power truly lay. These were not spirit ancestors of exemplary behaviour & divine judgement, but of empathy, compassion, & a deep abiding connection to the natural world; like the Christ they followed.

And where their stories are less compassionate, we can choose to reframe & rewrite them, not as a denial of their nature but as a reclamation & a reminder that these stories are always with us in one form or another, that they are alive. We can choose the door that we step through with open hearts and curiosity. St Mungo & his mother, St Teneu, are spirit ancestors who rewrote their own story; beginning in judgement & violence, they went on to become much loved & to found a city.

St Teneu, sometimes known as St Thaney or St Enoch, was a 6th Century Brittonic princess in the ancient kingdom of Gododdin (now Lothian). We know of her from the hagiography (or saint's biography) of her son, St Kentigern, aka. St Mungo, although she first appears in the Life of St Winifred, written in Wales in 1140. She is described as 'Scotland's first recorded rape victim, victim of domestic violence, & unmarried mother', a deeply distressing story, but one holding power & comfort for those experiencing, & standing against, the blight of violence in our society, because St Teneu survived and went on to thrive.

It's sometimes said that Teneu was raped by Owein man Urien. Often he is disguised as a woman, a theme which also appears in Arthurian myth when his mother, Igraine, is raped by Uther Pendragon using deceipt. In some stories Teneu chooses the relationship, sometimes Owain is already married, but there is no force. But no matter what Teneu did or did not do, it is she who is judged as having transgressed. There is an invitation here for exploring historical (& contemporary!) attitudes towards, & depictions of, our transgender siblings, & for examining beliefs around women's right to choose, amongst many other threads, but these are for another day.

On discovering that his daughter was pregnant, her father, King Lleudden, had her thrown off a cliff. But she was basalt-born, forged from volcanoes, and did not die. Instead, she was found and set adrift in a coracle, a small boat, without oars & left to the whim of the sea. Trusting the wild tides is another theme with our saints.

Travelling across the Firth of Forth, Teneu landed at Cuillean Ros (Culross), where she was taken in and cared for by St Serf. There she gave birth to her son, Kentigern ('Lord of Hounds'), more usually known as Mungo, a pet name meaning 'very dear one', so deeply loved was he.

Mungo studied under St Serf and, at the age of 25, set out to found a small church across the water from an extinct volcano, next to the Molendinar Burn, and where the City of Glasgow now stands. Here, after some toing & froing, he began to preach & drew a community around him. He was eventually buried there in 614 or 15 CE, having died at the age of 95. The spot is now marked by Glasgow's medieval cathedral, which also contains St Mungo's well.

Both St Teneu & St Mungo are much loved in Glasgow, & Mungo's 'four miracles', recounted in the rhyme at the beginning of this post, are depicted on the city's coat of arms. They also inspired musician Karin Polwart to write her song, 'Enough is Enough' for COP 26, which was held in Glasgow in November 2021.

The meaning of the stories is endlessly evolving ~

The Bird: Mungo is said to have restored a tame robin, the companion of St Serf, to life after his classmates killed it & sought to blame him.

The Tree: when still quite young, Mungo was left in charge of a fire in Saint Serf's monastery. He fell asleep and the fire went out. Taking a frozen hazel branch, he prayed over it until it burst into flame & he was able to relight the fire.

The Bell: the bell is thought to have been brought by Mungo from Rome. It was said to have been used in services and to mourn the dead. The symbol of the handbell has become synonymous with the City of Glasgow.

The Fish: refers to the story about Queen Languoreth of Strathclyde, who was faced with execution when her husband demanded to see a ring which she had given to a knight who had promptly lost it. She appealed for help to Mungo who, we might imagine was remembering the treatment that his own mother had endured, ordered a messenger to catch a fish in the river. On cutting the fish open, the ring was miraculously found inside, allowing the Queen to clear her name.

I especially love the saints who break through the divisions between us by caring for rich and poor alike.

St Swithun, whose Feast Day was just a few days ago on 15th July, has only one miracle credited to him during his life. One day in Winchester, a poor old woman was carrying a tray of eggs which she intended to sell at market. As she crossed a bridge she met some workmen who began to tease and jostle her. So upset was she that she dropped her tray and all the eggs, the source of her livelihood, were broken. Aggrieved, she made her way to the cathedral and told St Swithun what had happened. He listened to her complaint, gave her his blessing, and she found that the eggs were returned to their unbroken state.

Following his death, Swithun continued to protect women from all layers of society. There is a story that a female servant was condemned to be beaten for a minor misdeed. Whilst she waited overnight for her punishment she wept and prayed to St Swithun to be saved. As morning prayers began the next day the shackles that had been at her ankles broke open and she rushed to St Swithun’s shrine. She was then forgiven because the saint had interceded on her behalf.

But, although he often brought justice to the common people against the wishes of worldly authority, St Swithun also helped the rich and powerful. It’s said that in 1043 Queen Emma of Normandy was falsely accused of adultery. In order to prove her innocence she had to undergo the ordeal of walking over nine red-hot ploughshares. She spent the night in prayer at St Swithun’s shrine and the next day she was able to walk across the burning iron without harm.

Here is Swithun, whose name means ‘strong bear-cub’, protecting the falsely accused and beleaguered Feminine, bringing a warm summer rain of compassion to rich and poor alike. He is the saint to pray to in times of drought and certainly it feels that there is a drought of compassion now.

Returning to St Mungo & St Teneu, their stories are also recounted in a series of poems by poet laureate of Glasgow, Niall O'Gallagher. His poem, 'An T-Eun Nach D’rinn Sgèith (The Bird That Never Flew)', recounts the tale of St Mungo & the robin, here reimagined in a 1980s primary school playground;

NACH D’RINN SGÈITH

Laigh an t-eun gun ghluasad air an làr.

Thàinig iad nan gràisg: ‘Is ann a dh’eug

brù-dhearg, mharbh esan e’, ’n gille sèimh

a rinn iad a thrèigsinn mar bu ghnàth.

Cha tug e an aire ach, le gràdh,

A rinn e nead le làmhan agus shèid

anail shocair, thlàth air a dà sgèith

sgaoileadh beatha feadh gach ite ’s cnàmh’.

Dh’fhan i tiotan air a bhois

a’ ceilearadh air leth-chois

mus do thog i oirre tron an sgleò.

Theich a threud ach cha do chlisg

an gille le làmhan brisg’,

cluas sa lios ri bualadh sgèith an eòin.

THE BIRD THAT NEVER FLEW

The bird lies stock-still on the ground.

The gang moves in: “the robin’s deid –

he kilt him”. The quiet boy is betrayed,

as happens when stuff goes down,

but he pays no heed and lovingly

makes a nest with his hands and blows

soft, warm breath into her bones,

her feathers, and fills her wings with life.

She hovers an instant on his palms

on one leg, singing,

then takes off into the dark.

Everyone else long gone, the boy still cups his hands

and, unflinching,

listens for a wingbeat in the yard.

(Niall O'Gallagher, translated by Peter Mackay)

O'Gallagher goes on to say that;

"There is a thread in all these poems which is really about refugees. Here we have a mother and child fleeing violence, arriving in a new place where they don’t speak the language and haven’t two pennies to rub together. I think that’s a story many people living in Glasgow would relate to.”

Here is a story in which those who have found themselves outcast & in the most precarious of positions, are offered shelter and kindness and are able to rewrite their own story, giving hope to those of us whose own stories are a heavy weight to carry and who find themselves pushed to the edges of our society. St Mungo's Feast Day is on 13th January, approaching the end of Christmastide and reminding us to hold justice and kindness as our wise companions as we begin to tentatively re-emerge into the world from the womb of winter. St Teneu's is on 18th July, a reminder to carry those qualities into the soon-returning dark, to harvest compassion as a charm.

We are not what has happened to us, but what we are becoming. May we all have life breathed into us and reclaim our wild stories as seeds as we move towards Lammastide and harvest.

References:

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Teneu

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saint_Mungo

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Igraine

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swithun

https://orthochristian.com/122701.html