Reclaiming Catterntide: a Women's Winter Journey for Commoners' Advent

Commoners' Advent, day 10

Today has been Catterntide, such a special day in our journey through Commoners’ Advent, and one in which my community gathers to ‘Keep Cattern’, as our ancestors have done for hundreds of years.

Catterntide is another name for the Feast Day of St Catherine of Alexandria, who is said to have lived from 287-305 CE, but is much more likely to be an apocryphal figure, a collection of threads of memory of many women who died for their faith around that time. Nevertheless, she was, and is, an important figure for many; considered one of the 'Fourteen Holy Helpers' ~ a group of saints first written about in 14th Century Rhineland during the bubonic plague epidemic, which came to be known as the Black Death. The Fourteen Holy Helpers were considered to be especially effective when approached in prayer, particularly against certain diseases. In St Catherine's case, her intercession was sought especially against sudden death and diseases of the tongue, the latter because she was considered to be a fine orator, as we shall see.

Catherine was an extremely important saint during the late Middle Ages, and is considered by many to have been the most revered of the virgin martyrs. Her medieval cult was established when, in 800 CE, her body was allegedly rediscovered on Mt Sinai and said to be still growing hair and with healing oil flowing from her body. Several pilgrimage narratives detailing this rediscovery added to her legend and shrines and altars holding her relics sprang up all over England and France. Both Canterbury and Westminster claim to hold phials of her oil, brought back by Edward the Confessor, and St Catherine's Hill in Hampshire, which is the site of an Iron Age hill fort is topped by a 12th Century chapel dedicated to her.

There is another chapel, this time built in the 14th Century on St Catherine's Hill near the village of Artington, Surrey.

This chapel is very close to the River Wey and I once sought it out during my days living on a boat. We were unable to find the way and were guided there by the most beautiful grey cat, but that is perhaps a story for another day.

You can see St Catherine’s Chapel and hear about the riotous fayre that took place there in this video from 4:02.

It feels worth mentioning though that St Catherine's Hill forms part of the landscape feature known as the Hog's Back, which has sites dedicated to both St Catherine and St Martha. I once went to a talk at the, much missed, London Earth Mysteries Circle where the speaker told us that she believed the Hog's Back to be an example of the body of the Sacred Feminine lying in the landscape. At that talk a fellow attendee shared that he considered St Catherine, who name means 'light' or 'pure', to be a manifestation of Brighid. This connection with Brighid will become even more powerful when we consider St Catherine and the candle flame tomorrow.

Ean Begg, in his essential work, 'The Cult of the Black Virgin', tells us that St Martha sites mark the presence of pre-existing snake cults, with Martha having 'tamed the dragon'. Snakes are also sacred to Brighid, as folklore tells us that adders rise from hibernation on her Feast Day at Candlemas on 2nd February. Although this might not be directly relevant to our Advent journey I love the ways that the wild spirit weaves connections to make new and endlessly beautiful patterns.

But back to St Catherine and Catterntide. St Catherine attracted a large female following, who were less likely to make pilgrimage and more often held her up as an exemplar of ideal female behaviour; I hope that her fierce and intelligent debating skills were included in that! From the 14th Century her mystic marriage to Christ began to appear in hagiographies and in art, and the 15th Century Joan of Arc named her as one of the saints who appeared to and counselled her. That St Catherine is so deeply woven into female experience we shall see when we come to Catterntide but, first, we might hear about her life, according to the legends that have attached to her.

Catherine was born in Alexandria, Egypt in 287 CE as the daughter of Constus, the governor there during the reign of emperor Maximian. A studious child from a young age, a vision of Mary and Jesus caused her to convert to Christianity when still a teenager. When persecutions of Christians began under Maxentius, Catherine rebuked him for his cruelty using the example of Christ to persuade him to change his ways. Fifty of the emperor's most accomplished philosophers and orators were summoned to speak for him but could not best her in debate. Many converted to Christianity as a result and were executed immediately.

Catherine was cruelly beaten and imprisoned for twelve days. Such was the pity of those witnessing her treatment that they wept at the sight of her, but when the prison door was opened a bright light and beautiful perfume emanated from within and Catherine emerged looking more radiant than ever. It was said that during her incarceration angels brought her healing salve and that she was fed daily by a dove from Heaven, together with being visited by Christ.

As torture had not broken her, Maxentius proposed marriage, which she refused declaring Christ as her spouse. Furious, the emperor condemned her to death on the breaking wheel, subsequently referred to as a 'Catherine Wheel', but at her touch the wheel fell apart. Her beheading was ordered and when carried out it was said that a milk-like substance flowed from her neck.

Catherine's cult remained strong until at least the 18th Century, and she is still the subject of much devotion amongst Eastern Catholics and Eastern Orthodox Christians.

St Catherine's Feast Day on 25th November is celebrated in many cultures in many different ways, which seems perfectly understandable when we consider that she is the patron saint of unmarried girls, craftspeople who work with a wheel ~ spinners, potters etc ~ archivists, dying people, educators, jurists, knife sharpeners, lawyers, librarians, mechanics, theologians, hat makers, nurses, preachers, haberdashers, philosophers, scribes, students, spinsters, tanners, and wheelwrights, among many others! But all the threads that move through her feast day meet in the life experiences of women and the dignity of women's work, as we shall see.

On St Catherine's Day in France it is the custom for young women to pray for a husband, and to honour 'Catharinettes'; those who have reached the age of 25 unmarried.

The women send postcards to one another and wear ostentatious hats, coloured green for faith and yellow for wisdom. They process to St Catherine's statue and ask for her to intercede for them lest the become spinsters and 'don St Catherine's bonnet'. I learned too this Catterntide that women entering menopause are said to have, ‘turned St Catherine’s corner’!

The focus on hats and bonnets has led St Catherine's Day to become a day when milliners hold a parade to show off their wares. A similar parade takes place in New Orleans the weekend before Thanksgiving.

In contrast, in the British Isles St Catherine and her Feast Day is almost entirely bound up with lace makers, who took Catterntide as an annual holiday and would save up a little money during the year to provide tea and cakes on the day, hence Cattern cakes. If you would like to make your own Cattern cakes to the traditional Tudor recipe you can find that here. I promise you that they are delicious!

Mrs Frederica Orlebar of Hinwick House, Podington (Bedfordshire) wrote an account of an attempted revival of Catterntide in 1887 which gives an idea of how a ‘Cattern Tea’ might be held;

“Cattern Tea.

In Podington and neighbouring villages the lacemakers have, within the memory of middle-aged people, ‘kept Cattern’, on December 6th – St. Catherine’s Day (Old Style).

I believe it was Catherine of Aragon who used to drink the waters of a mineral spring in Wellingborough, and who (as is supposed) introduced lace-making into Beds. The poor people know nothing of the Queen, only state that it was an old custom to keep ‘Cattern.’

The way was for the women to club together for a tea, paying 6d. apiece, which they could well afford when their lace brought them in 5s. or 6s. a week. The tea-drinking ceremony was called ‘washing the candle-block,’ but this was merely an expression. It really consisted in getting through a great deal of gossip, tea, and Cattern cakes – seed cakes of large size. Sugar balls went round as a matter of course. After tea they danced, just one old man whistling or fiddling for them, and ‘they enjoyed themselves like queens!

The entertainment ended with the cutting of a large apple pie, which they divided for supper. Their usual bedtime was about eight o’clock.”

There are other reports though of Catterners dressing as men, singing bawdy songs, and waylaying men in the street; turning the world upside down!

I was very excited today to find this hypnotic song, ‘Here Comes St Catherine’, here performed by Pete Castle, which is a traditional song sun by workhouse girls in Peterborough and Ware, and perhaps in other places too, at Catterntide as they processed through the town wearing white dresses and carrying candles.

“Here comes St Catherine, as fine as any queen,

With a coach and six horses, a comin’ to be seen.

And a spinning we will go, will go,

A spinning we will go…”

It reminds me of the waulking songs sung by tweed makers in the Scottish Highlands as they worked.

That St Catherine and lacemaking have become connected may be something of a confusion, as the connection may instead be with Catherine of Aragon, much loved Queen of England from 1509 to 1533. A fine needlewoman, she was credited with teaching lacemaking to the women of Bedfordshire, Buckinghamshire, and Northamptonshire, and is said to have burned all of her lace in order to give more work to lace makers.

In Medieval times Catterntide marked the beginning of Advent, although as we have previously explored, it sometimes began at Martinmas on 11th November. I have written of Martinmas which celebrates light in the form of lantern parades, stresses the importance of sharing with the poor during the winter, and, as we enter the season of 'Peace on Earth, commemorates a soldier who refused to fight. And then we come to Catterntide, so deeply embedded instead in women's work and celebrating the production of white-as-snow lace. These two saints provide us with a mindful gateway into the winter and to the season of Advent and Christmas, just as Plough Monday and Distaff Day, close to Epiphany and Twelfth Night in early January lead us out, again rooted in the concerns of men and women respectively.

Often these are said to be secular festivals, as are the Eastern European festivals below, which survived Communism exactly because they were considered neither spiritual nor political, but this is only so in a world that divides spirit from matter. For me these festivals join both, providing us with a thread to follow through the longing and joy of Advent and Christmas which is of the world, not set apart from it. This is the message of Christmas; that Spirit became, and endlessly becomes, matter and joins us in the mess and mayhem of our lives. What could be more spiritual, or more political?

And so we come to the Estonian festivals of Madripäev and Kadripäev, which take place on St Martin's and St Catherine's Feast Days respectively, not only reminding us again how intimately these two saints are intertwined, not only rooted in good work, but also marking the changing season, for here are the men's and women's festivals of winter. Kadripäev in particular is one of the most important days in the rural folk calendar and is still widely celebrated.

The 'Visit Estonia' website describes these festivals as 'autumn spiritual harvest holidays' and tells us that on both days, "children traditionally visited houses around the villages singing, telling riddles, and collecting sweets."

On Madri-eve, 10th November, the children choose a madiisa or 'father' to lead them in the festivities, and similarly on Kadri-eve a kadriema or 'mother' is chosen. The Madri-father wears dark clothes and leads a procession filled with noise; the banging of pots and pans and playing of musical instruments. Many of the participants also wear animal masks and their arrival at a house is said to bring harvest luck.

The day's revelleries end with a party where a goose is served.

In contrast, the Kadri-mother wears white, as do all the women, as a symbol of the snows of winter, and the traditional porridge, kama, peas, and beans are eaten, together with homemade beer.

Kadripäev's particular quality comes from its association with the kadrisants or 'kadri beggars', although both days involve dressing up, often on St Catherine's Day with men dressing as women, and going from door to door receiving treats in return for seasonal songs and blessings. You can see Kadripäev in action below.

On Madripäev these songs relate to the harvest, but on Kadripäev they refer to good luck with herds and flocks, especially sheep, through the winter, Kadri being the guardian spirit of the herds. And caring for them was primarily a concern of the women.

In order to protect the sheep, shearing was suspended between Martinmas and Catterntide, and no spinning or weaving could take take place on St Catherine's Day, often extending to knitting and sewing, echoing the lacemakers' holiday in the British Isles.

That all of these festivals, although manifesting in a variety of ways, are grounded in the seasonal change in work, and the dignity of that work, is clear but they are also rooted in the 'World Turned Upside Down', a reminder that, although this work must be done, we are not slaves and should not be treated as such, that the necessary tasks of society should be completed by common agreement, not through domination and exploitation.

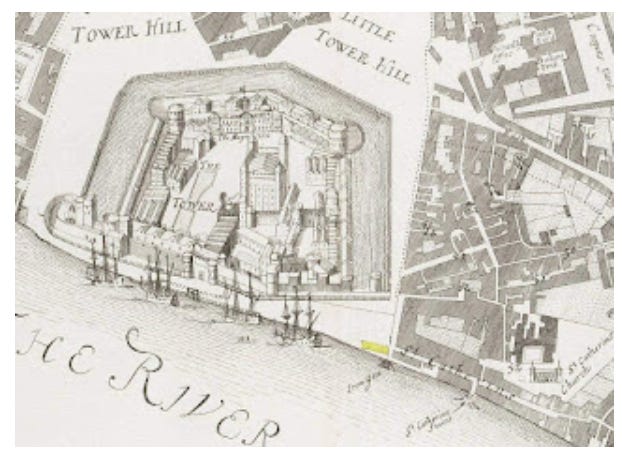

Which brings me briefly to the Liberty of St Katharine in London. In 1148, Queen Matilda purchased a piece of land close to the Tower of London and established a charitable hospice there. Unusually for that time the sisters and brothers who cared for the sick were considered equals. During the Reformation the site survived by being under the protection of the Queen and, in 1442, it became a 'Liberty', which meant that it was no longer subject to the laws of the City.

The Liberty of St Katharine grew to be a maze of narrow streets and lanes with up to 1,000 houses, cottages, and tenements. It attracted the outsiders of society; prostitutes, beggars, and many people who had come to England from other countries. Although poor and overcrowded, it is striking that the mortality rate in the Liberty during the Great Plague was half that of the surrounding areas. We might contrast this with the ways in which poorer areas during Covid-19 were disproportionately affected by the Coronavirus, their work being subject to bosses, rather than to themselves.

The Liberty of St Katharine was demolished for redevelopment following a much contested 1825 Act of Parliament. 1250 homes were destroyed and many made homeless without compensation. At the time many considered this to be desecration of a sacred site.

Although this is to be mourned, we might still celebrate the Liberty as an inspiring example of self-organisation, even with the most meagre of resources. This is a thread that runs through all connections with St Catherine, who was, like so many workers, threatened with being 'broken on the wheel' and who claimed her own dignity, despite countless attempts to dominate her.

As an aside the wonderful Foundation of St Katharine continues the work of bringing quietly subversive spirit to East London. I have visited there on retreat on several occasions and it is an oasis of green and calm in a sea of concrete. You can find out about them here.

This evening, the Wild Goose Collective gathered in the Little Church of Love of the World (on Zoom of course!) to celebrate Catterntide and to step through the gateway of winter. We learned about St Catherine and her feast day around the world, shared experiences, ate Cattern cakes, and reclaimed Catherine's Wheel as a symbol of strength. May it be so for us all. And it felt new, old, wild, and wonderful. Here I am in my Catterntide finery with today’s Advent candle.

Tomorrow, we will explore St Catherine as keeper of the winter candle flame, along with Old Clem and his midwinter forge as we follow the thread of fire through the darkling months, but until then I wish us all a very happy Catterntide!

References: See highlighted text.

#CommonersAdvent #OldAdvent #CelticAdvent #StMartinsLent #WinterLent

I am determined to continue offering my work free of charge, because that too is resistance, but if you would ever like to support me with pennies you can do that at https://ko-fi.com/radicalhoneybee. Thank you so much, both for pennies and for all other forms of support, all of which are worth more than their weight in gold.

How had I never heard of Catterntide?! For heaven's sake - I LIVED in New Orleans. And so many of the celebrations there like this made indelible impressions upon me. (St Joseph's Day for example) I adore your gift of this Commoners Advent series and it has become a cherished treat these cold and dark mornings.

How wonderful, thank you for sharing and for your research!