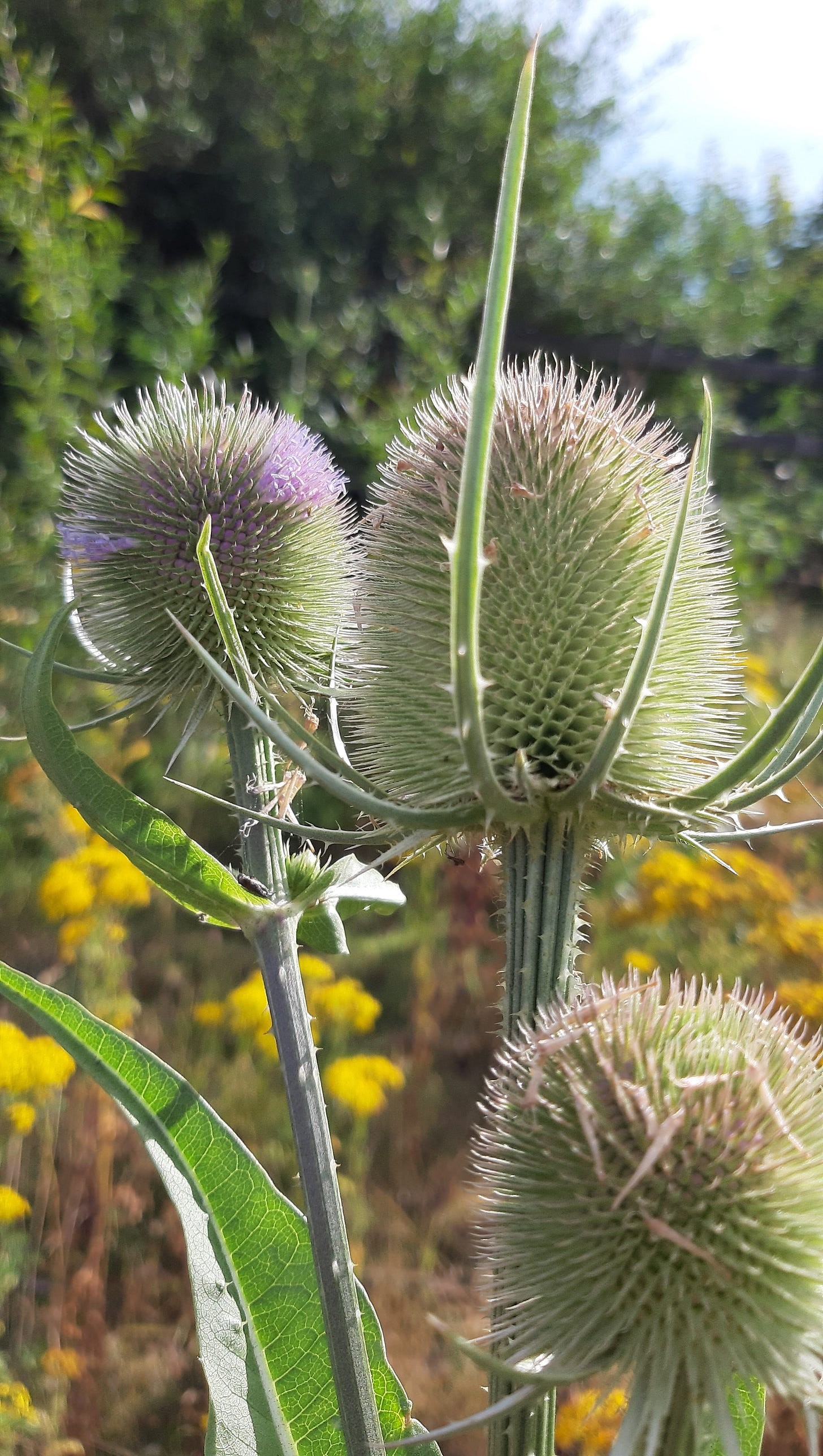

Here is Teasel. I have seen a lot of teasels this year & they always make me smile, probably because I remember teasel hedgehogs from when I was little. But these powerful plants are so much more fascinating than that.

Because, completely unexpectedly, teasels are one of our native carnivorous plants!

The teasel we are most familiar with is also known as wild teasel & fuller's teasel, the latter being a domesticated variety of the first. The fuller's (or draper's) teasel has more hooked spines on its flowerheads & so is helpful to the cloth industry, which we will learn about later. It is occasionally referred to as 'dipsacus sativua', with the more usual botanical name of both being 'dipsacus fullonum'.

'Dipsacus' comes from the Greek, 'to thirst', which refers to the way in which its leaves form a cup around the stalk.

This cup collects water, which is believed to offer the plant protection from sap-sucking insects crawling up the stem. The Romans called teasels 'Venus's Basin', & early Christians named them 'Mary's Basin' because of these little pools. Romany gypsies gathered this water & used it to soothe wrinkles & dark circles under the eyes. This echoes Culpepper (1616-64), who wrote that teasel tincture might be used for easing inflammations of the eye & as a cosmetic to ‘render the face fair’. Its roots have also been employed as an ointment to cure warts.

It's these pools which provide the teasel with nutrition from insects, although this process is still being studied. It's believed that the plant gains from absorbing the water in which trapped insects have rotted. Studies have shown that plants with more insects available produce more flowers & larger seeds. She is fed by holy composting wells.

As for teasel's further healing properties, although now rarely used an infusion of her root, harvested in early autumn, was said to strengthen the stomach, create an appetite, remove obstructions of the liver & treat jaundice. An infusion of her leaves has been used as a wash to treat acne, &, in folk medicine, she has been used as a treatment for cancer. She may also ease inflammatory conditions, such as arthritis. A sister species, Japanese teasel, which is called 'Xu Duan', which means, “restore what is broken”, has been used in Chinese medicine for thousands of years. Its root is used not only for arthritis, but also for blood circulation, kidney cleansing & the healing of damaged tissues.

Writer, Sylvia Lindsteadt, in her own piece on teasels, writes, "Now I see why the deer take big, eager bites from the teasel leaves. They know their own midwifery better than any of us. I’d bet it was the does, cleansing their blood, soothing their joints, after the weight of fawn-birth. None of this is to say that, at night, strange forms do not rise up from those basins, those carding-comb pods. Slight, tendriled figures that walk barefoot, dispense water from green leaf-bowls to mother creatures as they give birth—raccoons, squirrels, deer, snakes. Comb the burrs from their tails. Take the stray fur-pieces home and spin them into ropes for climbing down, down into the underworld, where necessary knowledge about rebirth, about chasing pain out of tight spaces, lives, pushed into deep quartz veins by the songs of moles."

Herbalist, Matthew Wood has suggested that teasel is helpful in treating Lyme disease by warming the joints & muscles where lyme bacteria settles, forcing them into the bloodstream where they can be killed by companion medicines. Fascinatingly, there is evidence that lyme-effective invasive plants, such as Japanese knotweed, are settling in places were Lyme disease is endemic. There is so much more vibrating in the web of life than we are aware of. We are not alone in our struggles.

Teasels are biennials, taking 2 years to complete their lifecycle. In the first year, their leaves form a rosette on the ground, with the texture of the leaves being compared to goose skin. In their second year, they grow a stalk, which can reach 6ft in height, & develop their impressive flowerheads. The resulting seeds provide a valuable winter food source for birds, especially goldfinches. It was this love of spiky seed-rich plants that led to goldfinches being named thisteltuige, or 'thistle-tweaker' in Anglo-Saxon times.

Teasel's common name, which comes from Old English tǣsl, tǣsel, relating to the verb "to tease", & the second part of its Latin name 'fullonum', referring to the work of a fuller, both derive from its traditional use as the 'teasing plant' of cloth workers. Some of her other folk names, for example brushes & combs & card thistle, also refer to this. Because teasel heads were once much prized by fullers as the perfect method to raise nap on cloth to soften it. The dried flower heads were once attached to a 'teasel cross' , & later to spindles, wheels, or cylinders, sometimes called teasel frames, to raise the nap on fabrics. After 'teazling', the raised fibres were then sheared by a cropper to produce fine cloth. It was, in part, the use of new cropping machines that caused the Luddite Rebellion to spread to Yorkshire in 1812.

So important were teasles to the woollen industry of the 18th Century that great fields, particularly in the Ridings of Yorkshire were turned over to their cultivation, with older growing fields in Somerset, Gloucestershire, & Worcestershire. Indeed, Yorkshire was not able to grow sufficient teasles for its needs & was often forced to bring in further supplies from elsewhere. Even before this rise of wool production, the 1582 Chamber Order Book of the City of Worcester warns that, "It is agreed that no walker shall use to wrangleholte (presumably 'tease') any brode clothe with wool cards nor with any other instrument but only a handle sett with teasells, in payne for the first offence 40s"! 'Wrangleholte' is definitely a new favourite word of mine!

Despite their importance, teasels were a risky crop & so deeply unpopular with land owners. Taking two years to flower, making heavy demands on the soil, & requiring constant weeding, teasle crops were not only slow but also vulnerable. If there was too much damp weather a whole crop might rot, too many teasles in a high yield year & their selling price would plummet. Because of this, the teasle industry developed an unusual system where the land would be ploughed & prepared before being rented to a 'tazzle man', a specialist teasle grower who would farm the crop & bear most of the risk. If successful, the profits would be shared between the farmer & the tazzle man equally.

In 1813, writer/illustrator George Walker, travelled through Yorkshire in order to document the clothing of ordinary, working people. He wrote that;

"The Teasel, or Dipsacus sativua, is a plant much cultivated in the east part of the West Riding, though form the impoverishing nature of the crop, which requires two years to bring to maturity, it is seldom approved by the proprieter of the soil. It is however and article of essential importance to the Colthier, who uses the crooked awns of the heads of this plact for raising the nap of the cloth. In the autumn of the second year the heads of the plant are cut off, carefully dried, and after being fixed upon long sticks, are conveyed away for sale. Temporary sheds are usually erected in the teasel fields for the work-people employed, who not unfrequently form very interesting groups."

Both woad & madder were grown amongst the teasels as companion plants. The Vale of York was a centre for the growth of both these important dye plants in the 19th Century, producing blue & red dyes respectively. Interestingly, George Walker's illustration of teasel workers from 1814 depicts them wearing blue & red aprons, cloaks, & scarves.

Penelope Hemingway in her blog on the British textile history, writes that the red cloak was, "the universal rural working class woman’s uniform". Teasels could also be used as a dye plant, providing a blue dye which was once used as an indigo substitute, &, mixed with alum, a rich yellow.

By the 20th century, teasels had been largely replaced by metal cards, which are uniform and do not require constant replacement. However, some wool weavers, particularly in the Scottish Borders, still prefer to use teasels for raising the nap & continue to work in the traditional way, saying that the result is finer & that teasels will not rip the cloth in the way that metal will if it meets a resistance in the fabric.

Teasels are no longer cultivated in the way that they once were but remain imposing, if little noticed, members of our edge-place communities, providing welcome nectar for bees & other pollinators. Even at the height of their use in cloth making, the lives of the working people who farmed them were little documented. It seems surprising for a plant that grows up to 6ft high that it somehow exists in a liminal world between remembering & forgetting. But, of course, it is also so with many of the undertakings of the common people who, save for the studies of a few clear-sighted individuals, were not considered worthy of study or recording. It is this attitude which made, & continues to make, it so easy for working people, such as the croppers & other textile workers of the 19th Century, to be cast aside in the name of endless 'progress' & riches for the few.

When we see a teasel standing tall we might remember our ancestors who themselves stood tall against Capitalism & its demands of increasingly cheap & unsustainable production, often risking, or even losing, their lives in doing so. Like Teasel, we have often been dismissed when we are no longer considered useful but, like Teasel, we too have a proud history that is worth remembering.

References:

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dipsacus

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dipsacus_fullonum

https://www.walkwithtrees.com/the-woodland-bard/teasel-dipsacus-fullonum

https://blog.adkinshistory.com/teasles/

https://theindigovat.blogspot.com/2012/06/magic-of-teasel.html

https://www.woodlands.co.uk/blog/woodland-flowers/pinkpurple-flowers/teasels/

https://pfaf.org/user/Plant.aspx?LatinName=Dipsacus+fullonum

https://www.plant-lore.com/teasel/

https://www.secretflowerlanguage.com/Flower/Teasel

https://theknittinggenie.com/2014/09/26/the-tazzle-man/

https://www.teazlesandteazlemen.co.uk/

http://returntonature.us/teasel-and-lyme/

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/science/2020/02/21/japanese-knotweed-could-key-fighting-lyme-disease/

https://blackcatsews.blogspot.com/2013/04/teasels-for-carding-myth.html

http://www.misin.msu.edu/facts/detail/?project=misin&id=161&cname=Fuller

https://www.botanical.com/botanical/mgmh/t/teazle09.html

https://www.indefenseofplants.com/blog/2017/9/20/evidence-of-carnivory-in-teasel