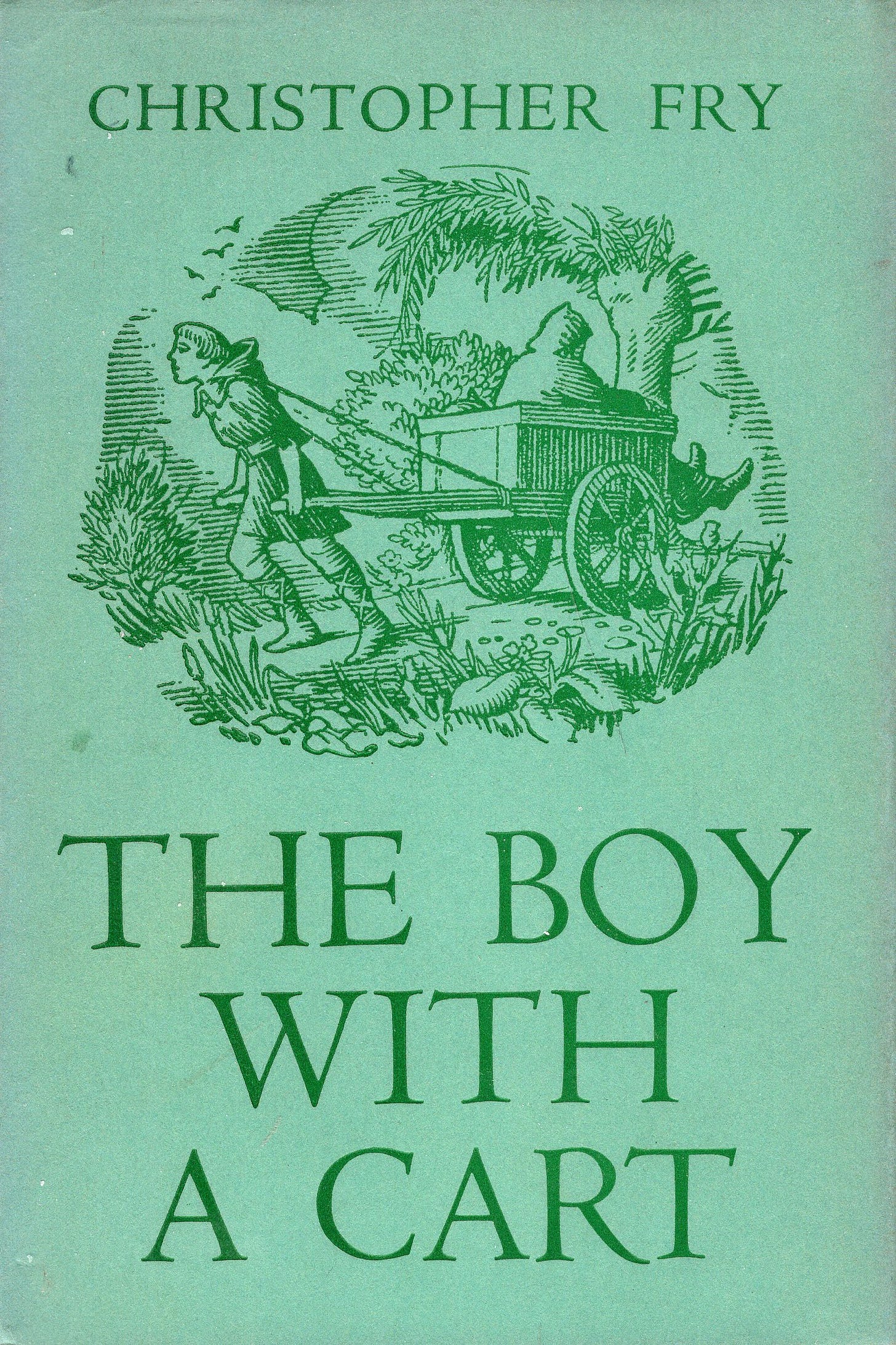

A Saint of Solidarity: Cuthmann of Steyning ~ The Boy With a Cart

This is the Wilderness We Choose; Our Lenten Journey, day 17

It is there in the story of Cuthman, the working together

Of man and God like root and sky; the son

Of a Cornish shepherd, Cuthman, the boy with a cart,

The boy we saw trudging the sheep-tracks with his mother

Mile upon mile over five counties; one

Fixed purpose biting his heels and lifting his heart.

We saw him; we saw him with a grass in his mouth, chewing

And travelling. We saw him building at last

A church among whortleberries…

(Christopher Fry, ‘The Boy With a Cart’, 1938)

I have written before that in my spiritual community, the Wild Goose Collective, we spend much time journeying with, and reflecting upon, the saints. Generally these are the pre-reformation saints of the early Anglo-Saxon period and Middle Ages, usually from the 5th and 6th Centuries when we were still allowed to believe in magic. 'Saint' can be an emotive word, and a divisive one, but we have come to love these often elusive tales of our holy ancestors; our ‘wild antlered saints’, who were close to the land and its beings, and we have found great wisdom and solidarity in our own struggles from learning about their lives.

One of our most beloved saints is Cuthmann of Steyning, a shepherd cast into poverty when his father died. His story is full of inspiration and wild heart but he is little known about. Last week, St Cuthmann was set against St Leoba in Lent Madness, which I wrote about in our Resource List for Lent, which you can find here. One of the reasons that participants gave for not voting for Cuthmann was that his story was ‘unverifiable’. Leoba was a woman of noble birth and a friend and colleague of St Boniface. Much is known about her. Yet another reminder that the poor are so often invisible, their histories lost or discounted, when set against those of privilege.

All I know is that, in St Cuthmann, many of our group have found an ancestor, ‘real’ or otherwise, who inspires us and who stands in solidarity with the vulnerable and those who seek to offer care and support in a world hungry for both. One of my favourite quotes, which I never tire of sharing, comes from W.H. Auden, who said, "animal femurs ascribed to saints who never existed, are still more holy than portraits of conquerors who, unfortunately, did." Just so.

And so to the story of St Cuthmann. In telling it I am indebted to the work of Roger Pearse who, over 2019/20, translated the Life of St Cuthmann from an original 11th Century manuscript. You can find his translation and notes here.

Roger Pearse writes that St Cuthmann is, “one of the few Anglo-Saxon saints who came from the lowest rung of society; he was a shepherd before being reduced to begging, as well as having to care for his mother. He remained a layman, and may have been illiterate.”

In his ‘Life’ we are told that Cuthmann was born in the chalk hills of Southern England around 681 CE. An innocent, devout, and studious child, he is said to have “avoided the blandishments of the world'“. At an early age he became a shepherd to his father’s sheep and was entrusted with their care when grazing in the nearby meadows. One day he had need to return home to collect food, but had not been given permission to take the sheep from their pasture. Not knowing what else to do, he drew a circle around them with his shepherd’s crook and prayed that they might be kept safe. When he returned, he found that the sheep had not moved beyond the boundary of his circle and were quite content. He continued to do this for several days when the necessity came for him to leave them. It’s believed that this may have taken place in a field around the village of Chidham in West Sussex, as for many centuries it was known as ‘St Cuthman’s Field’ or ‘St Cuthman’s Dell’. There was also a large stone in the field, ‘upon which the holy shepherd was accustomed to sit’, and which was ‘held in great veneration by the locals’ due to its miraculous properties.

St Cuthmann is also connected to legends surrounding the creation of the Devil’s Dyke, a 100 metre deep valley in the South Downs. Folklore tells us that the Devil was so angry at the conversion of England to Christianity; Sussex being the last of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms to embrace the new faith, that he resolved to drown its inhabitants by digging a trench so that the sea would flood in and engulf them. Hearing of this, Cuthmann offered the Devil a wager; if he could complete the trench in one night he could have Cuthmann’s soul, but if he failed he must leave the people of Sussex in peace forever. The Devil set about digging, forming a range of nearby hills, such as Chanctonbury Ring, together with the Isle of Wight. But shortly after midnight, Cuthmann tricked the Devil by shining a candle through a sieve and startling a cockrel so that it crowed in alarm. Believing that sunrise must have come, the Devil fled in disgrace leaving the trench unfinished.

As a little aside, I am interested in this story from the perspective of the seasons. St Cuthmann’s Feast Day is on 8th February, close to Imbolc-Candlemas; the time when the light has returned to the extent that, before electric lights, workers could now work by daylight rather than candlelight, and when candles for the year ahead would be taken to church to be blessed. I have recently learned about St Sillan, whose Feast Day is either on 28th February or 28th March, and whose Irish name, Sioláin, translates as either ‘seed-basket’ or ‘sieve’; both being objects used before the Agricultural Revolution to sow seeds in the fields. I want to write about St Sillan on another day, but for now I am drawn to this image of St Cuthmann with a candle in one hand and a sieve, or seed-basket, in the other, Candlemas to sowing time, accompanying us through this liminal time between the last days of winter and the edge of spring.

But that is not the story about St Cuthmann that I particularly wanted to share today. No, that story explains the title of this piece; ‘the Boy With a Cart’. When we left Cuthmann’s story, he was contentedly shepherding his family’s sheep but this contentment was not to last long because, quite suddenly, his father died. Following his father's death Cuthmann became a great support to his heartbroken mother; “the staff of her old age and the light of her eyes.”

Even so, and despite Cuthmann’s best efforts, the estate that had been left to them by his father was soon spent and he and his mother fell into near destitution. Bereft, his mother became weaker, losing the use of her limbs and becoming paralysed. She begged her son to leave her, but the more she did so the more devoted he became and the more affectionately he tried to help her. Now forced to beg from door to door, but unable to leave his mother, Cuthmann built a wooden cart, or wheelbarrow, and placed his mother in it. He fashioned a rope, which he hung across his shoulders to bear part of the weight, and pushed the cart in front of him. And so he was able to take his mother everywhere with him, until at last they decided to travel from the place that they had known all their lives, leaving ‘hearth and homeland’ and trusting to God.

The 14th Century Lustrell Psalter, which is unusual in depicting scenes of everyday life in medieval England, includes an image of a cart much like the one described in Cuthmann’s story.

During their journey, Cuthmann and his mother crossed a meadow in which some men were cutting the grass. It was then that the rope helping Cuthmann to carry his mother broke. Initially, Cuthmann was unsure what to do to remedy this misfortune, but then confidently cut a branch from a nearby elder tree (sometimes said to be willow) and made himself a new rope. The watching men found this hilarious, mocking him for using a material that was so easily broken, and were taught a lesson for their lack of heart when a large raincloud appeared, ruined their work, and chased them all the way home. The Life of St Cuthmann tells us that, ‘posterity so deplores their laughter’ that at every year at hay-making time there is rain in that field even to this day.

Seeing the men punished for their cruel jibes, Cuthmann thanked God and resolved to build a church in thanks. Then he carried on his way, sustaining himself and his mother by transporting goods from place to place and by begging. We are told that finally, “after untold hardship of hunger and thirst, and troublesome toils of many-fold fatigues”, mother and son came to Steyning in West Sussex. There the rope broke again and the wheelbarrow tipped over. Seeing that his mother was unhurt, Cuthmann understood that this was where he must build his church.

Understanding that God was, “caring for the careful” and lifted up the humble, Cuthmann’s greatest wish was to provide a place where others in need could pray and receive help. And so, seeing that this place, “enclosed by the streams of two springs descending from the mountain”, marked the end of his wandering, Cuthmann first built a wooden hut to shelter him and his mother and then set about building his church.

Being poor and inexperienced in building, and knowing that he could not achieve his task alone, Cuthmann was supported and helped by the community, who not only assisted with the building, but generously fed him and his mother from their own scant resources. So blessed was their work that they are said to have received help installing a roof beam from Christ himself! There remains a church, now dedicated to St Andrew and St Cuthman, on the site to this day. And, outside, looking towards the church he made, is a statue of St Cuthmann.

Cuthmann was venerated in Steyning long before the Norman Conquest. Indeed, in the Charters of William the Conqueror, the village is often referred to as ‘St Cuthman’s Port’ or ‘St Cuthman’s Parish’.

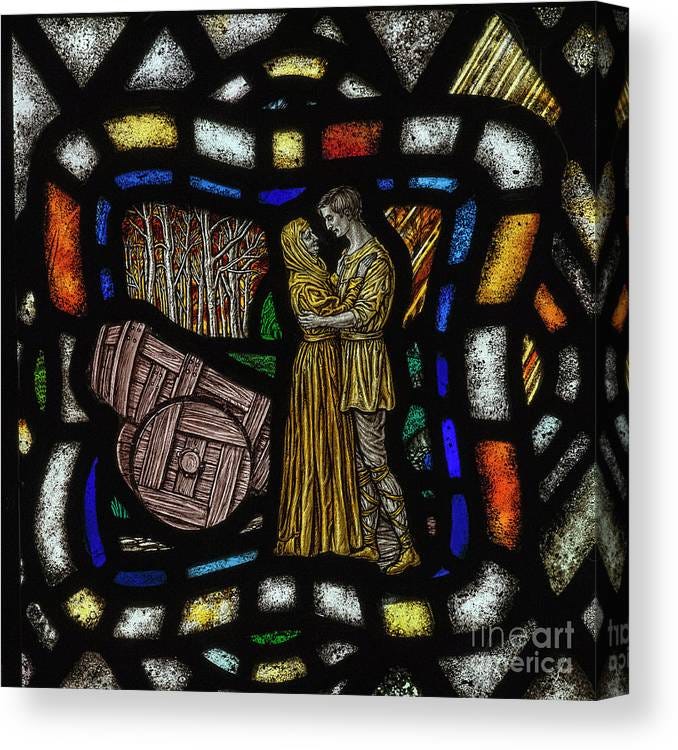

Considering that he is so deeply entwined with the landscape of West Sussex, it is surprising to note that, due to his relics (bones) being moved to the Abbey of Fécamp in Normandy, he became popular on the continent and that his Feast Day was celebrated in many of the religious houses there. So popular was he that, in 1450, German engraver and painter, Martin Schongauer, “the most important printmaker North of the Alps before Albrecht Dürer”, created an engraving of Cuthmann with his cart. He is also depicted in a 15th Century choir seat in Ripon Cathedral and, in 1522, a ‘Guild of St Cuthman’ in Chidham, his birthplace, was subject to a tax under Henry VIII.

Truly, a forgotten saint of the poor who rose to high places. I’m sure that he would be astonished. But what touches and inspires me most about St Cuthmann is his care for his disabled mother. At a time when many were starving, he chose to take her with him everywhere, caring for her no matter what misfortunes befell them. I know that there are members of my community caring for loved ones with disabilities and who find great comfort, inspiration, strength, and solidarity in the example of St Cuthmann.

There is an apocryphal tale attributed to anthropologist Margaret Mead, who is said to have been asked by a student what she considered to be the first sign of civilisation in a culture. Her answer? Not tools or clay pots, but a thighbone (femur) that had been broken and then healed. She explained that in nature very few animals survive with a broken leg long enough for it to heal. A healed thighbone is evidence that someone cared enough to stay with and tend the injured person, to bind the wound, to protect and to provide. Helping others is where civilisation starts.

Whilst acknowledging that there are certainly other-than-human beings who care for members of their community when they are injured or unwell, and that the whole concept of ‘civilisation’ is rather a muddy one, there is also much evidence of humans doing caring for the vulnerable back to our earliest origins. One example comes from Man Bac, a site in what is now northern Vietnam, at which archaeologists, Lorraine Tilley and Marc Oxenham, found the body of a profoundly ill young man who lived 4,000 years ago. Unlike the majority of other burials, he was buried curled in the fetal position, because his fused vertebrae and weak bones meant that he died as he had lived, deeply disabled and bent over by disease. Evidence showed that he had been suffering from a disease called Klippel-Feil Syndrome, which had paralysed him from the waist down before adolescence. Although he would have had little use of his arms and could not have fed or cleaned himself, he lived for at least another decade. The only possible conclusion is that the people around him had cared for him and kept him alive.

Lorna Tilley writes that among archaeological finds there are at least thirty examples of individuals who were so disabled that they would have needed constant care in order to survive, and that the number of cases in which support was offered is innumerable. There is a burial at a Neanderthal site in Iraq, dating from 45,000 years ago, of someone was severely disabled by the amputation of one arm and loss of vision in one eye but survived to the age of 50. There is a 10,000 year old burial in Italy of a boy suffering from severe dwarfism who was able to survive in a nomadic hunter-gatherer society despite the physical challenges he faced. ‘Windover Boy’, who lived 7,500 years ago in what is now Florida, suffered from Spina Bifida and survived until the age of around 15.

Disability activist, Sophie Macklin, has written about the body of a woman found at a burial site in Germany who lived 9,000 years ago. She was discovered buried with high status grave goods and marked with red ochre. It was found that she suffered from profound disability; a birth defect in her neck which would have affected her ability to care for herself and may have led her to experience altered states due to restricted blood flow to her brain. Our long ago ancestors did not abandon their ill and disabled loved ones. St Cuthmann is another in a long line of examples that we might wish to live by.

At the beginning of the Covid-19 lockdown I was being deeply moved by the determination of people to protect and help one another; to reach out to neighbours, to put others before themselves. It was the best of us shining through in the most difficult circumstances. Even nature was able to breathe out and thrive, with plants I had never seen before growing all around me on unmown verges. But that feeling was short-lived, replaced by a concern that the ability to, even slightly, put ourselves out on behalf of others has been bred out of us by Thatcherism & years of Tory rule. We seem to have no sense of the threads of connection between us, no sense of responsibility to others if it means inconveniencing ourselves, even in the most trivial of ways. Our sense of self-entitlement is vast, even amongst kind & caring people. Sometimes we have to accept less to allow others to have what is justly theirs.

This concept; of accepting less for the good of the collective, is one that we will have to come to terms with more & more as climate change takes hold & many people are no longer able to survive in their own lands. Our privilege has caused this. We have a responsibility. It is so often our health & privilege that offers us the choices we have, and sometimes we must make choices that we would rather not make for those who have no choice at all.

Rupa Fish, wrote in reaction to the Covid pandemic and wildfires in her native San Franscisco, that;

“When Covid ripped through SF, I thought to myself “OK, now we will look out for one another.” I was wrong…

When wildfire smoke caused the AQI to soar past 400 during the Delta surge that was packing the hospital to its brim, we started to see data that smoke exposure made Covid outcomes worse. “Ok,” I thought, “now we will get everyone in.”

No. Not even climate disaster. Not a pandemic. Not even both of these at the same time. Our lack of regard for one another has been the biggest moral injury I have sustained in these past few years. With the longterm impact of Covid in my chest, when I see this disregard of humanity continue, I feel tightness. I can feel my heart breaking, not at once, but fiber by fiber, as if it was unraveling.

What will it take for us to restore a sense of human sanity? For us to look at one another remember how deeply fragile and interconnected we are? How many intersecting disasters do we need to get everyone inside? We haven’t seen enough suffering, apparently. And that brings me great sadness, because it means that many more will have to die, have to endure horrific conditions and degradation of dignity before we come to our senses.

The disasters we are facing will give us many more opportunities to rub raw the callous that has crusted over the heart of humanity through colonial capitalist mentality, that has relegated some lives more worthy than others.

May these disasters excoriate the hardness of our hearts thoroughly, so that we can work together to get everyone inside. We have forgotten who we are.

We urgently must remember."

We need all the examples of care that we can get in order to do that. So many people truly are kind and I have seen that often since I have had a disability myself, but as a society we have forgotten so much about caring for others who are more vulnerable than ourselves, and both those needing care and the carers are so easily forgotten. St Cuthmann and his mother are a door to remembering, a door to a kinder, more compassionate way of being.

Margaret Thatcher told us that there was 'no such thing as society' & did all that she could to make that true. I have dedicated my life to proving her wrong. This is where we make our stand. I pray that we choose to remember the threads that hold us to one another & to all life.

It is there in the story of Cuthman, the working together

Of man and God like root and sky; the son

Of a Cornish shepherd, Cuthman, the boy with a cart,

The boy we saw trudging the sheep-tracks with his mother

Mile upon mile over five counties; one

Fixed purpose biting his heels and lifting his heart.

We saw him; we saw him with a grass in his mouth, chewing

And travelling. We saw him building at last

A church among whortleberries…

(Christopher Fry, ‘The Boy With a Cart’, 1938)

References:

St Cuthmann and his landscape ~

https://www.roger-pearse.com/weblog/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Cuthman-Life-BHL-2035.pdf

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cuthmann_of_Steyning

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Devil%27s_Dyke,_Sussex

https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/visit/sussex/devils-dyke/the-history-of-devils-dyke

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steyning

https://www.lentmadness.org/2023/03/cuthmann-of-steyning-v-leoba/comment-page-3/#comments

https://nonsenselit.com/2020/06/04/the-original-wheelbarrow-woman/

https://britishpilgrimage.org/portfolio/3-havant-to-chichester-mudflats-and-seabird-song/

https://westbournedeanery.wordpress.com/2013/06/29/chidham-st-marys-church/

https://steyningparishchurch.org/cuthman/

Disability and care ~

https://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/18/science/ancient-bones-that-tell-a-story-of-compassion.html

http://www.disabilityhistoryscotland.co.uk/timeline-early-history/

https://www.disabilityhistory-ancientworld.com/

https://www.denverpost.com/2012/12/17/archaeologists-find-prehistoric-humans-cared-for-sick-and-disabled/

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/deformed-skull-of-prehistoric-child-suggests-that-early-humans-cared-for-disabled-children

https://www.discovermagazine.com/planet-earth/82-humans-took-care-of-the-disabled-over-500-000-years-ago

https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2020/06/17/878896381/ancient-bones-offer-clues-to-how-long-ago-humans-cared-for-the-vulnerable

https://www.upi.com/Archives/1987/11/04/Cavemen-took-care-of-physically-disabled/5137563000400/

https://www.medicaldaily.com/ancient-bones-show-caring-disabled-old-society-itself-243999

https://www.amsvans.com/blog/compassion-for-people-with-disabilities-shown-in-ancient-bones

https://www.iflscience.com/prehistoric-graves-filled-with-treasure-show-huntergatherers-cared-for-their-disabled-children-46112

http://peoplethinkingaction.blogspot.com/2013/01/disability-in-prehistory.html?m=1

https://gizmodo.com/neanderthals-with-disabilities-survived-through-social-1819801216

https://thesebonesofmine.wordpress.com/2013/09/10/interview-with-lorna-tilley-on-the-bioarchaeology-of-care-methodology/

https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1987/11/09/skeleton-of-dwarf-shows-ancients-cared-for-disabled/6e9bc007-018d-423f-b6e0-62afc6ae587e/

https://www.advalvas.vu.nl/en/blog/care-our-most-vulnerable

https://www.forbes.com/sites/kristinakillgrove/2016/01/12/young-woman-with-disabilities-found-in-artifact-packed-bronze-age-burial/?sh=a27ab084bbac

https://historicengland.org.uk/research/inclusive-heritage/disability-history/

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/03/180313130443.htm

https://connect.springerpub.com/content/book/978-0-8261-8063-6/part/part01/chapter/ch01

What a fabulous piece of research and writing Jacqueline! Thank you. I am enriched today by your words, and feel huge love and respect for St Cuthmann as a shining

example of the compassion humans can show when living their ‘best lives’ in the truest sense X